'타인에겐 자비로워야’ 습관적으로 배워

가족들에겐 자비의 마음 나누는데 인색

|

서양 불자들 사이에서는 불교 공부에 전념하는 수행자들이 일년에 한두 번 정도 집중적인 묵언 명상의 안거에 참여하는 것이 매우 일상화 되어 있다. 6년 전, 첫 아이가 태어나기 이전까지 나는 아주 규칙적으로 안거 수행에 참여했었다. 나의 아이들이 자라서 3살, 5살이 되자 일주일 정도 아이들 곁을 떠나 있는 것도 괜찮을 것이라고 느꼈다. 그리하여 나는 지난해 12월, 7일간의 묵언 안거수행에 참여했고 모든 것은 잘 진행됐다. 엄마가 된 지 5년 만에 다시금 집중 수행에 참여한다는 것은 정말로 멋진 일이었다. 나는 그 수행을 통해 많이 변했다. 삶을 바라보는 관점은 훨씬 더 풍부하게 다듬어졌다. 안거 수행이라는 배경에서 마주하는 불교의 가르침들은 훨씬 더 살아있고, 진실하게 느껴졌다. 그러한 과정에서 얻게 된 통찰력은 깊이가 있었고 또한 지속적인 것이었다. 그런 까닭에 올 여름에는 9일간의 안거를 신청했다.

노스캐롤라이나에서 매사추세츠주의 시골마을로 안거 수행을 위해 여행을 떠나기 하루 전날 저녁, 내게 기쁨을 가져다주는 ‘그을린 빛깔’의 아기를 안고 있었다. 아기를 안고 있으니 나는 갑자기 떠나지 않고 싶어졌다. 그 생각에 스스로 놀라면서 모든 일정을 취소할까도 생각했다. 하지만 그런 감정은 엄마로서의 집착이라고 생각하면서 이내 떨쳐버렸다. 불교에서는 이를 어떻게 설명하는지도 알고 있다.

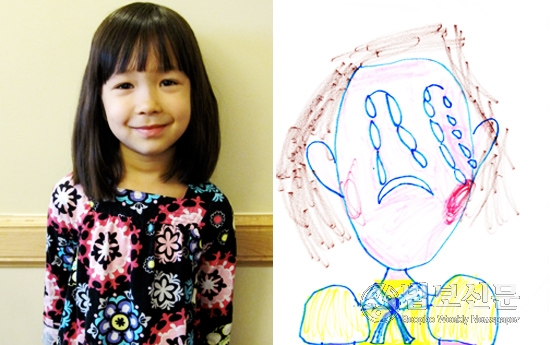

비행기 속에서 휴대용 컴퓨터를 꺼내면서 내 딸 ‘프리야’(Priya)가 내가 모르는 사이 나의 배낭에다가 그림을 그려놓은 것을 발견했다. 여기 그림이 있다.

“이런, 아가야! 엄마와 떨어진다는 것이 너에게는 정말로 혼란스러웠던 게로구나.”

그리 생각하니 다시금 나는 마음의 갈등을 떨쳐버려야 했다.

“모든 아이들은 부모를 놓아버리는 걸 배워야 해. 내 딸도 그렇게 할 거야.”

안거 수행센터에 도착해 나는 절친한 친구의 사무실로 갔다. 1970년대에 젊은 엄마가 되자 그녀는 명상센터에서 그녀의 아들을 길렀다. 센터에는 2000명가량이 머물고 있었고 아이들은 여러 사람들이 공동으로 보살피고 있었고 종종 부모로부터 격리되기도 했다. 그러한 상황에 대해 친구는 후회하고 있었다. 친구는 자신의 영적인 추구에 너무나도 강하게 몰입한 나머지 그녀의 아들이 성장하면서 함께 했어야 할 시간을 놓쳐버린 것에 대해 후회한다고 고백했다. 그날 오후 담소를 나누면서 그녀는 아들이 막 6살이 되려던 해에 왜 아들과 함께하지 못했는지에 대한 이야기를 들려주었다.

안정이 되자 곧바로 나는 안거수행에 빠져들었다. 단지 9일의 여유 밖에 없었고 내가 성취해야 할 목표는 아주 많았다. 나는 무아(無我)를 체험하고 싶었고 ‘온전한 깨어있음’을 경험하고 싶었다. 하지만 첫 몇 번의 명상시간에 나는 참을 수 없을 만큼 고통스러웠다. 이전에는 미처 겪어보지 못한 형태로 나의 몸은 아팠다. 나는 행선(行禪)을 매우 싫어했다. 정해진 수행 일과표에 따르는 것을 거부하기 시작했다. 그래도 나는 여전히 나 자신을 통제하고 있었고, 명상 수행 동안 말 그대로 이를 악물고 ‘나’를 발견했다. 이전의 안거 수행에서 나는 통상 쉽게 안정이 되었고 비록 마음이 흐트러지기도 했으나 집중과 ‘마음챙김’ 수행의 토대를 세울 수 있었다. 그러한 과정을 거치면서 통찰력도 얻었다.

저녁 법문 시간에 한 법사가 자기는 30년간 수행을 해왔다고 말했다. 앞으로도 안거 수행을 계속 할 것이라고도 했다.

“아직까지 당신의 마음을 깨닫지 못했나요? 궁구할 것이 얼마나 더 남아 있나요? 마음을 깨닫고 나면 왜 계속해서 안거수행을 해야 할 필요가 있나요? 깨닫고 난 다음에는 그것의 적용, 윤리 등이 그 이후의 실제 과제가 아닌가요?”

나는 그러한 생각에 집중하면서 그곳에 앉아 있었다. 그날 밤 늦게 침대에서 뒤척이면서 집중해서 생각했다.

“마음챙김 수행의 비법을 배우고 이를 일상생활에 성공적으로 적용하고 나면 도대체 집중적인 안거 수행이 무슨 소용이 있는가, 수행의 실제 과제는 타인을 위한 우리의 행위와 배려에 놓여 있는 것이 아닐까?”

나는 이전에는 불교 안거수행에 대해 이런 종류의 비판적인 생각을 가져본 적이 없었다. 집중적인 안거 수행에 대한 모든 신념은 나에게는 환상 같이 느껴졌다. 곧바로 이런 형태의 사고는 ‘의심’이라는 수행의 장애에 해당된다고 깨달았다. 그것은 불처럼 나의 마음을 휩쓸고 있었다. 그것을 관(觀) 하기 위해 ‘마음챙김’ 수행법으로 의심에 대해 궁구하기 시작했다. 나는 다소간 안심이 되고 이해를 할 수 있었지만 의심은 떠나지 않았다. 곧이어 “여기에 더 이상 머물고 싶지 않아”라는 생각에 사로잡혔고 나는 그것을 어떤 중요한 통찰력을 막 얻게 되는 순간이라고 확신했다. 그래서 그 수행에 더욱 더 나를 몰입하게 했다. 기이하게도 ‘가행 정진한다’는 이 순간, 나의 수행은 내가 얼마나 완벽하게 현재의 순간에 몰입할 수 있는지를 보고자 하는 것이었다. 그런데 그 결과, 안거 수행에 대해 알레르기 반응을 일으키는 것처럼 상황을 더욱 악화시켜 버렸다.

앞으로 남아있는 5일간을 생각해 보니, 그것은 내게 매시간 행선과 좌선의 황량한 반복으로만 다가왔다.

“내가 일상생활에서 더욱 풍부하고 완벽하게 배우지 못해 여기서 배우겠다는 것이 도대체 무엇이지?”

나는 의아해졌다.

“내 자녀에게 소리 지르게 하는 상황을 만들어내는 인과에 대해 안거 수행에서 보다는 일상에서 더 많이 배우는데.”

하지만 포기하려는 결정을 내리기 전, “자비수행으로 전환해보는 건 어떨까, 의심이라는 장애의 속박이 완화되고 수행의 기쁨을 다시금 찾게 해 줄 수도 있을 거야”라고 생각했다. 다음 번 명상 시간에, 여러 부류의 자비 수행 대상들에 대해 검토했고 흥미롭게도, 또한 무의식적으로 나의 어머니를 대상의 한 사람으로 포함시키게 되었다. 이전에는 어머니를 대상으로 자비수행을 해 본 적이 없었다. 끝으로 수행 중에 쌓은 공덕이 모든 이에게 회향되도록 했다. 이 자비심이 세상으로 퍼져나가는 것을 느끼자, 레이더에 나타나는 대상물처럼 내 딸 ‘프리야’가 그곳에 있는 것이 아닌가. 바로 그 순간, 모든 것이 나에게는 완벽하게 명확해졌다. 어떤 의문점도 남김없이 나의 문제가 무엇이었고 앞으로 무엇을 해야 할지를 알게 되었다.

몇 달 전, 불교에 관한 짧은 글을 가족들을 위해 썼다. 글을 쓰면서 많은 불교 센터들은 자녀와 부모를 분리시켰고 부모들은 함께 모여 명상수행을 했고 자녀들에게는 별개의 프로그램이 운영되고 있다는 것을 알게 되었다. 이런 방식도 좋긴 하지만 모든 가족 구성원들이 함께 수행할 수 있는 좀더 효율적인 형태를 제시했다. 부모와 자녀의 경우 비록 각자 구분되는 수행과정이 필요한 것도 사실이지만 같은 주제에 대해 함께 몰입한다면 가족 구성원 모두가 함께 성장할 수도 있을 것이다. 예를 들면 일주일가량 ‘바른 말’에 대해 함께 살펴 볼 수 있을 것이다. 즉 부모와 자녀는 일상생활을 해 나가는 중에 바른 말을 한 순간과 바르지 못한 말을 한 순간들을 서로에게 지적해주게 된다. 이것이 불자 가족들을 위해 내가 도입한 ‘비전’이다. 부모와 자녀는 함께 성장하고 서로에게서 배운다. 우리가 자녀에게 가르칠 것이 많듯이 자녀들 또한 부모에게 마찬가지 역할을 한다.

나 자신에게 나의 수행에 대해 질문을 던져야만 했다. 내가 가족을 떠나 고립되어 수행을 하고 있는 것이 그 비전의 실현에 어떤 형태로 기여하고 있는가? 여기서 나는 상호 연관을 가르치고 있지만, 사실은 상호 단절을 수행하고 있다. 엄마의 영적인 길은 곧 버림, 슬픔, 떠남과 동일한 것이라고 ‘프리야’가 믿도록 바랐는가? 떠남을 통해 나는 삶의 우선순위에 대해, 특히 내 딸의 우선순위에 대해 어떻게 설명할 것인가? 선원에서와 같은 지금의 이 안거 수행형태는 주부로서, 부모로서, 엄마로서 나의 인생의 이 시점에서는 적합하지 않았다. “그래 나중에는 적절한 상황에서 돌아 올 수 있을 거야, 그러나 지금은 아니야. 나의 자녀가 저렇게 어린 동안은 아니야.”

|

개인적인 수행을 위해 일년에 두 차례씩 가족을 떠나야 하는 이런 방식 대신에 그와 다른 새로운 방법이 떠올랐다.

“우리 가족이 함께 안거 수행을 하는 거야. 이것은 ‘나만의’ 영적인 길이 아니라 ‘우리’의 길이 되는 것이야.”

나는 그러한 방법이 현명하다고 확신한다.

수미런던 듀크 불교공동체 지도법사 simplysumi@gmail.com

번역 백영일 위원 yipaik@wooribank.com

다음은 영어원고 전문.

Homecoming

Among Western Buddhists, it’s fairly common for dedicated students of the dharma to do one or two intensive, silent meditation retreats a year. I too went on retreat fairly regularly until I my first child was born about six years ago But, once our kids reached ages 3 and 5, I felt they would be fine if I was away for a week or so. As such, last December I went on a 7-day silent retreat and all went well. It was fascinating to do intensive meditation practice after five years of motherhood: I had changed a lot, and my perspective on life was much more richly textured. I found the dharma teachings, particularly in the context of retreat, much more alive and relevant. Some of the insights that arose, too, were deep and enduring. As such, I registered for a 9-day retreat this summer, expecting to pick up where I left off.

The evening before I was to fly up from North Carolina to rural Massachusetts, as I held my beautiful, brown children in my arms, I suddenly felt that I didn’t want to go. Surprised by the thought, I considered cancelling altogether, but I dismissed the feeling as simply mother’s attachment ? and we know what Buddhism has to say about that!

On the plane, as I took out my laptop, I saw that my daughter Priya had put a drawing in my backpack without my knowing it. Here is the drawing. “Oh dear,” I thought, “this is really upsetting for her.” Again I dismissed the tug in my heart: “All children must learn to let go of their parents, she will adjust.” When I got to the retreat center, I went to the office of one of my best friends who had, when she was a young mother, raised her son in a meditation center in the 70s. The center had about 2,000 residents, and the children were taken care of communally and often separate from their parents. As a result, my friend has reflected on her regret that she was so into her own spiritual path that she missed some of these years of being with her son as he grew up. In our chat that afternoon, she again told a story of how she had not been present for a special moment that happened when her son was about six years old.

After settling in, I wasted no time plunging right into retreat mode. Only 9 days and I had a lot to “accomplish.” I wanted to taste non-self and to experience pure awareness. Within the first few meditations, however, I began to suffer tremendously. My body ached in ways it never had before, I absolutely hated walking meditation, and I began to rebel against following the schedule. Still, I disciplined myself and found myself literally gritting my teeth through meditations. In previous retreats, I normally settled in easily and, though my mind wandered, I was able to establish a foundation of concentration and mindfulness that did yield insights.

During an evening dharma talk, one teacher mentioned that he had been practicing for thirty years. He also said he continues to go on retreat. I sat there wondering, “Don’t you know your mind by now? How much is there to explore? And once you know your mind, why do you still need to do retreats? Isn’t the rest of it really about application, about ethics?” Later that evening while tossing and turning in bed I thought, “Once you have learned the trick of mindfulness and successfully carried the practice over into daily life, what is the use of intensive retreat? Isn’t the real challenge of learning in our conduct and care for others?”

I had never had these kinds of critical thoughts about Buddhist retreats before. The whole idea of intensive retreat seemed to me an illusion. Soon after, I recognized this kind of thinking as the hindrance of doubt, which was sweeping my mind like a fire. I began working with doubt, using mindfulness to observe it. Although I found some relief and understanding, doubt would not go away. Soon thoughts of “I don’t want to be here” came up, which at first I took as a sign that I could be on the verge of a major insight and so forced myself to work harder at practice ? ironically my form of working harder was to see just how fully I could let go into the present moment. If anything, this made things worse, as if I were having an allergic reaction to the retreat.

As I looked at the five remaining days ahead, all I saw was a kind of bleak hour-after-hour of walking and sitting. “What am I learning here that I am not learning more richly and completely in daily life?” I wondered. “I am learning more about the causes and conditions that give rise to the moment in which I yell at my kids than I am with this.” (In the last half year, I sought to examine why I yell and, as a result of this understanding, I hardly yell at my kids any more.) Yet, before deciding to give up, I thought, “Why don’t I switch to metta (loving-friendliness) practice? Perhaps this will loosen the grip of doubt and restore joy to my practice.” The next sit, I went through the categories, interestingly and unconsciously choosing my mother for one of them. I had never done metta for my mother before. Finally, I allowed the goodwill accumulated during that sit to extend outward to all beings. And as I felt this metta radiate out into the world, like an object appearing on a radar there was Priya. At that very moment, everything became completely clear to me and I knew, I knew without any doubt, what my problem had been and what to do next.

A few months ago, I finished a short chapter on Buddhism for families. As I wrote, it came to me that many Buddhist centers split the children and parents, so that the parents can do meditation together while the children have their own program. Although this model is good, I had envisioned a more integrated system in which the whole family is practicing together. Although parents and children do indeed need their separate classes, the whole family could grow if we engaged the same topic together. For example, we could take a week to look at right speech, with parents and children reflecting to each other moments of right and also not-right speech as the business of the day goes along. And this is the vision I use for the Buddhist Families of Durham: parents and children growing together and learning from each other. Children have as much to teach us as we do them.

I had to ask myself, now on retreat, in what way did my leaving my family, practicing in isolation, serve that vision? Here I was preaching connection but practicing, in fact, disconnection. Did I want Priya to equate her mother’s spiritual path with abandonment, with sadness, with departure? What did my leaving say about my priorities, and my daughter’s placement in the rank of priorities? As a householder, as a parent, as a mother, I saw that this form of practice ? intensive and monastic-like retreat practice ? was not the right form at this time in my life. Later, yes, I will be well served to return, but not now, not while my kids are so young. In place of this idea that I would leave the family twice a year for personal practice formed a new vision. Our family should do retreats together. This would not be “my” spiritual path but “our” path. This model felt wholesome, appropriate, skillful, and wise.

With this clarity in mind, I met with one of the retreat teachers, herself a mother of four now-grown children. When I told her I needed to break retreat and why, she completely understood. She told me a story of a time when her youngest daughter was 4, about twenty-plus years ago. She had been invited to a teacher training far from home. She arrived, began the training, and called her daughter to check in. “But mommy,” said her daughter, “you will miss my first soccer practice!” She left the training that day or the next to return home: “As a mother,” she said, “you know what your first priority is.” I later met with other teachers and staff, and the ones who had not had children tended to conclude I was leaving because I missed my children or that they needed me. Not so. I can leave for a week and it’s not a problem for either of us. But leaving to find some kind of nirvana -- that is a problem, emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually.

About ten years ago, before I had children, I read an essay by a man who grew up in a Zen center in New York in the 1970s. He wrote,

[My parents] search for enlightenment was constant…. We will be a better family through kensho [awakening]. Not by missing one evening sitting or going to the movies for a change, but by going to the sitting [meditation] and leaving me with the babysitter, again.

The reflection touched me because I too had had parents who spent hundreds of hours in silent meditation, not playing with me, not being with me, and at times, not raising me. The unintended message I heard as a child was that “I am cutting you off in order to be a kinder, more compassionate parent” is very strange, indeed.

As I flew back home to North Carolina, I could taste the sweetness of the dharma again. It had grown bitter in my mouth during the time I struggled with a question I was not even aware I had. I also reflected on how it was the metta practice that helped me gain clarity. I saw that sometimes there are limits to working with the mind and that it is the heart that knows the truth.